Posts Tagged ‘War Is Beautiful’

War Is Beautiful by David Shields

Forty years ago, Susan Sontag, in an essay for the New York Review of Books, wrote,

“To photograph people is to violate them… Just as a camera is a sublimation of a gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder.”

This backed her argument that photography was “essentially an act of non-intervention” that shared “complicity” in “another person’s pain or misfortune”.

Susan Sontag noted that Nick Ut’s (Huỳnh Công Út) photo of Kim Phuc, a naked South Vietnamese girl with arms spread, wracked in pain from napalm,

‘Did more to increase the public revulsion against

the war than a hundred hours of televised barbarities’

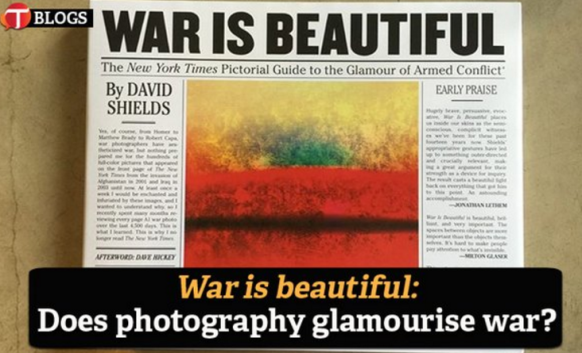

These essays formed On Photography, such nuance earned it the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977, and it became one of the most important works of literary criticism on photography in the 20th century. The latest addition to this, in a book Noam Chomsky calls “Shattering,” is David Shields’ War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict. To provoke, Shields provides 64 photos taken from The New York Times, 1997-2014, with a brief essay on how Shields dissected thousands of images from front pages. Shields writes:

“Over time I realized these photos glorified war through an unrelenting parade of beautiful images whose function is to sanctify the accompanying descriptions of battle, death, destruction, and displacement.”

His conclusion:

“I found my original take corroborated: the governing ethos was unmistakably one that glamorized war and the sacrifices made in the service of war.”

Shields’ epiphanies lead him to accuse Judith Miller and the Times of,

“—intimate participation in the promotion of the war (that) led directly to immeasurable Iraqi death and destruction”.

Therefore he will,

“No longer read the New York Times”.

Does Shields think substantive benefits would come from such a proclamation?

I don’t.

Shields and I have combated ideas for years, leading to the collaboration on a book and film I Think You’re Totally Wrong: A Quarrel, as well as a curmudgeonly friendship. My understanding of his modus operandi leads me to suspect posturing and intentional irony in displaying the same photos that ‘glamorized’ war to enhance his art, the cover (reminiscent of Rothko) an example. Shields does not deny how photography has contributed to progress, from Mathew Brady’s Civil War black and whites, Walker Stevens’ pictures of the Depression era South, to the contributions of Robert Capa (who died after he stepped on a mine in Vietnam). His focus is only the Times.

The photos hold significance and power, separated into ten chapters, ‘Nature’, ‘Playground’, ‘Father’, ‘God’, ‘Pietà’, ‘Painting’, ‘Movie’, ‘Beauty’, ‘Love’, and ‘Death’, framed with quotes from Cormac McCarthy to Gore Vidal, the majority taken in Afghanistan and Iraq post 9/11, but also some from Aleppo, Bosnia, Gaza, Islamabad, and Arlington National Cemetery.

A soldier’s camouflaged helmet peeks out of a field of pink and white poppies in Afghanistan, an Israeli tank enters Gaza underneath clouds and dust, a niqabi walks in the rust ochre air on a Baghdad street; a crushed piano sits amidst rubble in Saddam Hussein’s son’s palace.

A soldier’s camouflaged helmet peeks out of a field of pink and white poppies in Afghanistan, an Israeli tank enters Gaza underneath clouds and dust, a niqabi walks in the rust ochre air on a Baghdad street; a crushed piano sits amidst rubble in Saddam Hussein’s son’s palace.

The most beautiful photos, though, display humanity, Shavali refugees in the ruins of the Russian Embassy in Kabul, street girls in Islamabad, an Israeli woman holding a toddler in one arm and leading another through a blood splattered hallway, a Palestinian holding a dying child in Gaza, a marine doctor in Iraq cradling an infant in pink, and Ali Hadi, a professional body washer, preparing a corpse in Najaf, Iraq, as relatives of the deceased watch. Let’s take a look at the selected photos:

They are definitely beautiful.

Do these images propagandize war or elicit revulsion? Does the photo of a one-armed woman bouncing a ball with her physical therapist at Walter Reed Medical Center lead “to immeasurable Iraqi death and destruction?” or to the question, “Was her sacrifice worthy?” In many cases, the verdicts embedded in Shields’ essay fail to complement the photos.

Shields, whose most profound line here is “war is a force that gives us meaning,” taken from Chris Hedges anti-war book, has judged before acknowledging paradox. What Bertolt Brecht wrote in 1931, “Photography, in the hands of the bourgeoisie, has become a terrible weapon against the truth,” contradicts how Don McCullin’s images of the Biafran War caught the attention of the French Red Cross and helped lead to the formation of Doctors Without Borders in 1971. John Berger and Roland Barthes questioned the ethics of photography, Diane Arbus may have exploited her subjects, but withheld judgment.

Shields, whose most profound line here is “war is a force that gives us meaning,” taken from Chris Hedges anti-war book, has judged before acknowledging paradox. What Bertolt Brecht wrote in 1931, “Photography, in the hands of the bourgeoisie, has become a terrible weapon against the truth,” contradicts how Don McCullin’s images of the Biafran War caught the attention of the French Red Cross and helped lead to the formation of Doctors Without Borders in 1971. John Berger and Roland Barthes questioned the ethics of photography, Diane Arbus may have exploited her subjects, but withheld judgment.

The relevance of beauty in Shields’ framework, also, betrays his argument. The clumsiness of four Sonderkommando photos does not take away from their spectral and accidental beauty, or the pathos. Should Gilles Peress or Allan Sekula or Sebastião Salgado have been better off using grainy blurred images? Visceral beauty promotes bellicosity as easily as it promotes pacifism.

But Shields will not budge as he asks “Who is culpable?” His answer a bromide, “We all are.” Sigh. Walter Benjamin wrote,

“There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a documentation of barbarism.”

Documentation demands involvement.

What did Nick Ut do after taking his Pulitzer Prize winning photo?

He rushed Kim Phuc to the hospital. I’d wager that most New York Times photojournalists, with encouragement from their higher ups, would have done the same.

(This review is a reprint, previously published at The Express Tribune Blogs)

Written by Caleb Powell

June 14, 2016 at 6:05 am